Using Socket Sharding in KDB-X for Load Balancing and High Availability

This guide teaches you how to use socket sharding in KDB-X to load balance connections, scale services dynamically, and perform zero-downtime rolling updates using the Linux SO_REUSEPORT option.

Overview

In this guide, you will learn how to implement and leverage socket sharding in KDB-X. We will cover:

- Enable socket sharding: How to activate socket sharding from the command line or within a q session

- Use cases and implementation patterns: Practical examples of load balancing, dynamic scaling, and high availability

- Performance and behavior considerations: Key insights into how the kernel distributes connections and what it means for your application

- Summary: A recap of the skills and concepts covered

Enable socket sharding

Linux kernel requirement

Socket sharding in KDB-X relies on the SO_REUSEPORT socket option, which was introduced in Linux kernel version 3.9. The commands and examples in this guide will fail if you run them on an older version of Linux.

To enable socket sharding, you use the rp (reuse port) parameter when specifying the listening port for a KDB-X process. This instructs KDB-X to set the SO_REUSEPORT option, allowing multiple processes to listen on the same IP address and port simultaneously.

You can enable this feature either when starting a process or from within an active q session.

From the command line

Use the -p command-line argument with the rp parameter. This starts a q process listening on port 5000 with socket sharding enabled.

$ q -p rp,5000

From within a q session

Use the \p system command with the rp parameter.

q)\p rp,5000

Sharding requires the rp option on all processes

If a process binds to a port without the rp option, all other processes will fail to bind to that port, regardless of whether they use the rp option. This results in an 'Address already in use error.

For example, if the port is already open without rp:

q)// First process opens the port normally

q)\p 5000

q)// A second process tries to use rp, but fails

q)\p rp,5000

'5000: Address already in use

Use cases and implementation patterns

Socket sharding enables several patterns for managing server load and improving system availability. When a connection request arrives, the Linux kernel distributes it across the listening processes, acting as a simple and effective load balancer.

Basic load balancing

The most direct use of socket sharding is to distribute incoming client connections across a group of identical KDB-X processes. This is especially effective for improving throughput for high volumes of short-lived requests.

Let's see it in action.

1. Set up the listeners

Start four separate KDB-X processes. In each one, enable socket sharding on port 5000.

q)// Run this in four separate q sessions

q)\p rp,5000

2. Open client connections

From a fifth client process, open 1000 connections to the shared port.

q)// Initialize an empty list to store connection handles

q)h:()

q)// Open 1000 connections to the shared port 5000

q){h,:hopen `::5000} each til 1000;

3. Verify the distribution

Now, let's check how many connections each server process received. We can do this by grouping the handles by their process ID (.z.i).

q)// Count the number of connections handled by each server PID (PIDs will vary)

q)count each group {x ".z.i"} each h

32219| 250

32217| 257

32213| 245

32215| 248

The output shows the connections are distributed almost evenly across the four processes. While the kernel does not guarantee a perfect distribution, it effectively spreads the load.

Improved throughput and response time

In tests where a client sends a high volume of requests, moving from one to three listeners can significantly increase the total number of requests processed and improve the overall average response time.

Dynamic scaling to handle increased demand

You can add new listener processes to a running system to dynamically handle increased load without any service interruption.

In this scenario, a client sends one request per second to a process group where each request takes two seconds to process. We'll start with one process and add more over time to see the impact.

Client code

The client sends an asynchronous message every second and records the round-trip time for each message.

// Create a table to store timing data

messages:([]sendTime:();receiveTime:();timeTaken:())

// Timer function: runs every second to send one message

.z.ts:{

st:.z.T; // Record the send time

h:hopen 5000;

// Send the message asynchronously, with a callback to record results

(neg h)({(neg .z.w)({(x;.z.T;.z.T-x;hclose .z.w)}; x)}; st)

}

// Set asynchronous message handler to update our table

// with time recordings

.z.ps:{0N!list:3#value x;`messages insert list}

// Start the timer to run every 1000ms

\t 1000

Listener code

Each listener process simulates a long-running query by sleeping for two seconds.

// Enable socket sharding on port 5000

\p rp,5000

// A simple counter for received messages

cnt:0

// Async message handler: sleep, execute callback, then increment counter

.z.ps:{

system "sleep 2"; // Simulate a 2-second task

value x; // Execute the client's callback

cnt+:1;

};

Results

We start with one listener. After one minute, we start a second listener, and after two minutes, a third. We can compare the average response time by querying the message logs on one-minute buckets:

q)1#messages

sendTime receiveTime timeTaken

--------------------------------------

19:34:10.514 19:34:12.517 00:00:02.003

q)// Normalize data into 3 distinct 1 minute buckets by

q)// subtracting 10.514 from sendTime column

q)select `time$avg timeTaken by sendTime.minute from update sendTime-00:00:10.514 from messages

second | timeTaken

--------| ------------

19:34:00| 00:00:03.909

19:35:00| 00:00:03.494

19:36:00| 00:00:02.628

| Minute | Number of Listeners | Average Requests Processed | Average Response Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 31 | 3.909 |

| 2 | 2 | 42.33 | 3.356 |

| 3 | 3 | 55 | 2.607 |

Table 1: Requests processed and response time when listeners are added on the fly 1 minute apart

As we add more listeners, the average response time decreases and the total number of processed requests increases. The Linux kernel routes new connections to available listeners, bypassing those blocked by the two-second sleep.

High availability via rolling updates

Socket sharding allows you to perform rolling updates on your KDB-X processes with minimal service downtime. This is ideal for services with long startup times, such as a historical database (HDB).

By using the socket sharding, you can start a new HDB process on the exact same port as the running HDB and avoid any downtime.

HDB script

This script simulates an HDB that takes 30 seconds to load before it can accept connections.

// Enable socket sharding

\p rp,5000

// Helper function for logging with timestamps

stdout:{0N!(string .z.T)," : ",x}

// Log new connections and disconnections

.z.po:{stdout "Connection established from handle ",string x}

.z.pc:{stdout "Connect lost to handle ",string x}

stdout "Starting HDB load... (simulated 30s)"

system "sleep 30"

stdout "HDB load complete. Ready for connections."

Client script

This client includes robust retry logic. If the connection drops, it immediately attempts to reconnect.

// Helper function for logging with timestamps

stdout:{0N!(string .z.T)," : ",x}

// Connection function with exponential backoff retry logic

.util.connect:{

tms:2 xexp til 4; // Tries with waits of 1, 2, 4, 8 seconds

while[(not h:@[hopen;5000;0]) and count tms;

stdout "Connection failed, waiting ",

(string first tms), " seconds before retrying...";

system "sleep ",string first tms;

tms:1_tms;

];

$[0=h;

stdout "Connection failed after 4 attempts, exiting.";

stdout "Connection established"];

h }

// On peer disconnect, attempt to reconnect immediately

.z.pc:{

stdout "Connection lost to HDB, attempting to reconnect...";

.util.connect[] }

// Initial connection

h:.util.connect[]

Rolling update procedure

To achieve a seamless update

- Start HDB.1: Run the HDB script

- Start client: The client connects after the 30-second load time

- Start HDB.2: While HDB.1 is running, start a new instance of the HDB script on the same port (

rp,5000) - Stop HDB.1: Once you see the log message "HDB load complete" on the HDB.2 console, safely shutdown the HDB.1 process

-

Client failover:

- The client's connection to HDB.1 is closed, which triggers its

.z.pchandler - The client executes

.util.connect[] - The connection is instantly successful because HDB.2 is fully-loaded

- The client's connection to HDB.1 is closed, which triggers its

Outcome: The client avoids the 30-second maintenance window entirely, experiencing only a sub-second network reconnection.

This process ensures the client only experiences a brief disconnection instead of the full 30-second HDB load time, achieving high availability.

Performance and behavior considerations

While powerful, it's important to understand that the Linux kernel (not KDB-X) handles the connection distribution. This distribution is not guaranteed to be round-robin and is not aware of the application-level state (e.g., "busy" or "idle") of the listening processes.

Behavior with a busy listener

This example shows what happens when one of two listeners becomes blocked.

Listener code

Each listener logs the time it receives a message.

// Set port number to 5000

\p rp,5000

// Create table to store time and message counter

messages:([]time:();counter:())

// Define synchronous message handler to store time and

// message count in messages table

.z.pg:{`messages insert (.z.T;x)}

Client code

The client sends a new synchronous request every second.

cnt:0

.z.ts:{cnt+:1; h:hopen 5000; h(cnt); hclose h}

\t 1000

During the test, we manually block one of the two listeners for 10 seconds.

q)// In one of the listener sessions:

q)system "sleep 10"

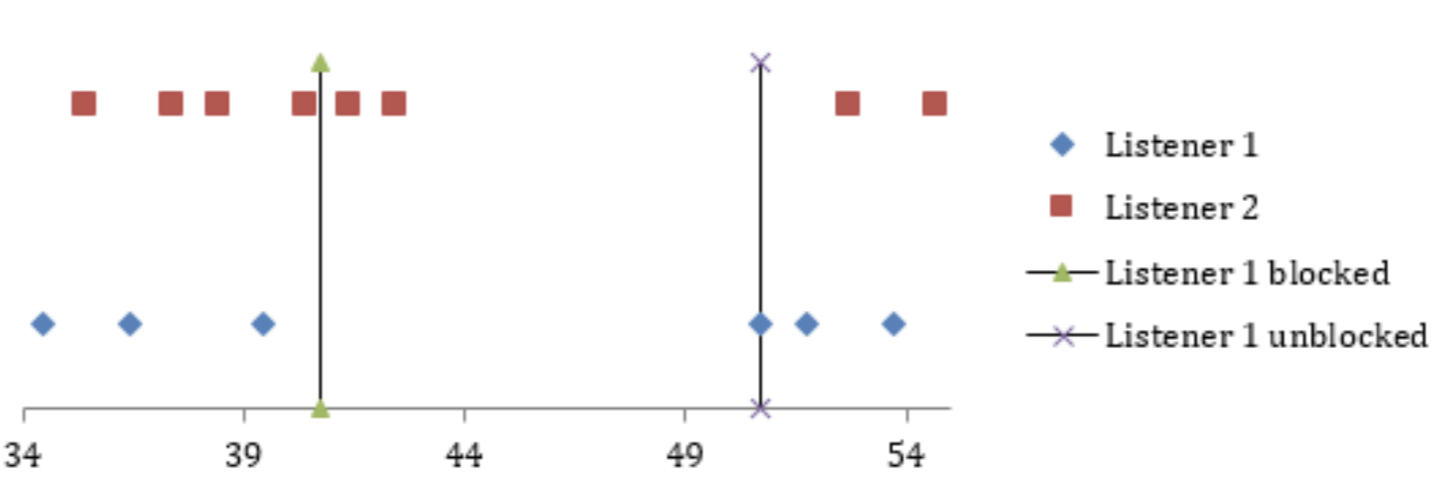

Observation

While one listener is blocked, the kernel may still route a new connection request to it. If this happens, the client will hang until that listener becomes available and accepts the connection. During this time, other connection requests might be successfully routed to the other, available listener and be processed immediately.

This demonstrates that socket sharding effectively distributes load but does not prevent clients from being routed to a temporarily unresponsive process. Your client-side logic should always account for potential connection delays or timeouts.

Figure 1: Graphical representation of the timeline of requests from the client to server processes

Summary

In this guide, you:

- Learned how to enable socket sharding in KDB-X using the

rpport parameter - Implemented a basic load balancing pattern to distribute connections across multiple processes

- Discovered how to dynamically scale a service by adding new listeners to handle increased load

- Performed a rolling update of a stateful service to minimize downtime

- Understood the kernel's role in connection distribution and its performance implications

Reference

This guide is based on the original whitepaper on socket sharding with kdb+ and Linux. For additional details and the original research, see:

- Socket sharding with kdb+ and Linux - Original whitepaper by Marcus Clarke