Implicit iteration¶

Before you specify iteration, see whether what you need is already implicit in the operators and keywords

This tutorial as a video presentation

Lists and dictionaries are first-class entities in q, and most operators and keywords iterate through them. This article is about when to leave it to q.

That is, when not to specify iteration.

Recall:

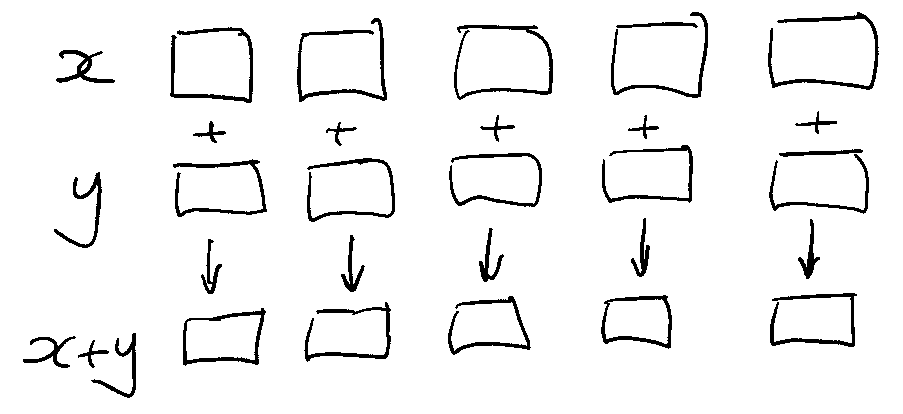

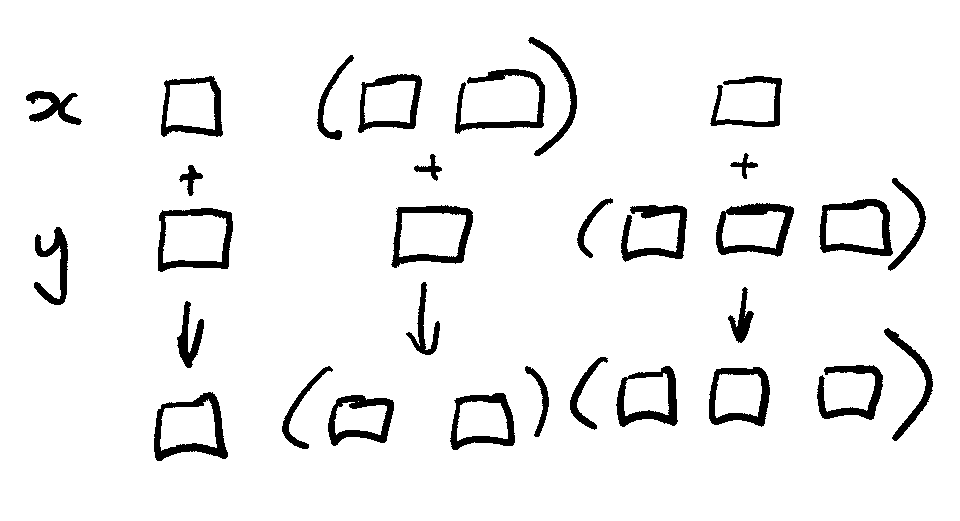

- Map iteration

-

evaluates an expression once on each item in a list or dictionary.

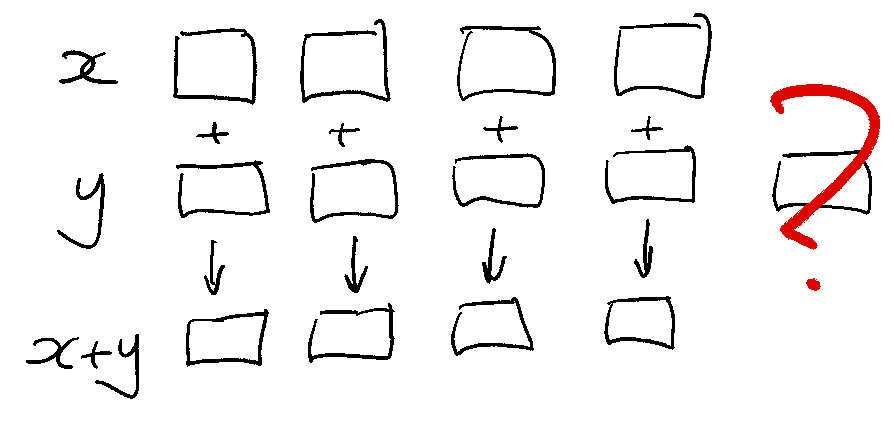

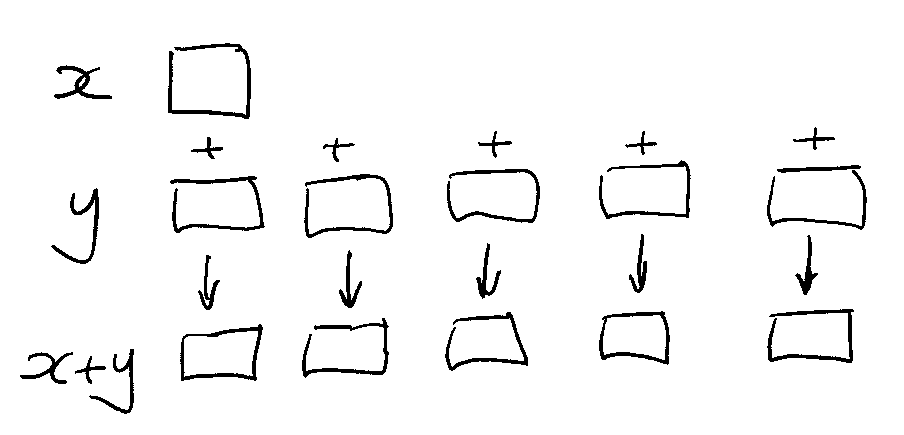

- Accumulator iteration

-

evaluates an expression successively: the result of one evaluation becomes an argument of the next.

Implicit map iterations¶

The simplest and most common implicit map iteration is pairwise: between corresponding list items.

q)10 100 1000 * (1 2 3;4 5 6;7 8)

10 20 30

400 500 600

7000 8000

q)10 100 1000 * (1 2 3;4 5 6)

'length

[0] 10 100 1000 * (1 2 3;4 5 6)

^Scalar extension¶

Unless! If one of the operands is an atom, scalar extension pairs it with every list item.

q)5 < 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

00000111b

q)"f" < ("abc";"def";"gh")

000b

000b

11bAtomic iteration¶

Many operators have atomic iteration: they iterate recursively, pairwise and with scalar extension, until they find the atoms in a list.

q)1 4 7 < (1 2 3;4 5 6;7 8)

011b

011b

01b

q)(1;2 3 4; 7) < (1 2 3;4 5 6;7 8)

011b

111b

01b

q)(1;2 3 4;(5 6 7;8)) < (1 2 3;4 5 6;7 8)

011b

111b

(110b;0b)q)cos (1 2 3; 4 5 6)

0.5403023 -0.4161468 -0.9899925

-0.6536436 0.2836622 0.9601703

q)lower("THE";("Quick";"Brown");"FOX")

"the"

("quick";"brown")

"fox"4 < (1;2 3 4;(5 6 7;8))

0b

000b

(111b;1b)within is an ascending pair of sortable type.

But in its left domain, within is atomic.

q)2 3 4 within 3 6

011b

q)(2 3 4;(5; 6 7;8)) within 3 6

0 1 1

1b 10b 0bList iteration¶

List iteration is through list items only – not atomic.

The like keyword has list iteration in its left domain.

q)`quick like "qu?ck"

1b

q)`quick`quack`quark like "qu?ck" / list iteration

110b

q)(`quick;`quack`quark) like "qu?ck" / but not atomic

'type

[0] (`quick;`quack`quark) like "qu?ck"

^Simple visualizations¶

Even a simple visual display can be useful. Here are sines of the first twenty positive integers, tested to see which of them is greater than 0.5.

q).5 < sin 1 + til 20

11000011000001100001bWe can take that boolean vector and use it to index a short string, getting us a simple visual display.

And, as you probably know, Index At @ can be elided and replaced with prefix notation.

q)".#" @ .5 < sin 1 + til 20

"##....##.....##....#"

q)".#" .5 < sin 1 + til 20

"##....##.....##....#"Index At is atomic in its right domain; that is, right-atomic.

Here we’ll index a string with an integer vector and we’ll get a string result.

q)" -|+" @ 0 3 1 1 1 3 0

" +---+ "q)" -|+" @ (0 3 1 1 1 3 0;0 2 0 0 0 2 0)

" +---+ "

" | | "q)(0 3 1 1 1 3 0;0 2 0 0 0 2 0) @ 0 1 1 1 0

0 3 1 1 1 3 0

0 2 0 0 0 2 0

0 2 0 0 0 2 0

0 2 0 0 0 2 0

0 3 1 1 1 3 0q)" -|+" @(0 3 1 1 1 3 0;0 2 0 0 0 2 0) @ 0 1 1 1 0

" +---+ "

" | | "

" | | "

" | | "

" +---+ "q)show L:("the";"quick";"brown";"fox")

"the"

"quick"

"brown"

"fox"

q)(1 3;2 0)

1 3

2 0

q)L@(1 3;2 0)

"quick" "fox"

"brown" "the"

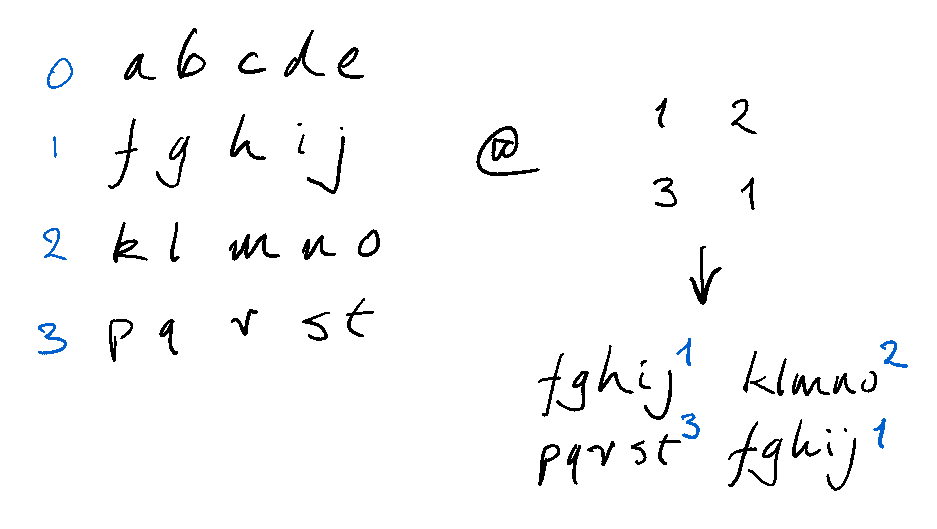

q)show q:4 5#.Q.a

"abcde"

"fghij"

"klmno"

"pqrst"

q)q @ (1 2;3 1) / Index At: right-atomic

"fghij" "klmno"

"pqrst" "fghij"

q)q . (1 2;3 1) / Index: list iteration on the right

"ig"

"nl"q)deltas 1 5 0 9 5 2

1 4 -5 9 -4 -3

q)ratios 2 3 4 5

2 1.5 1.333333 1.25Exercise 1¶

sensors.txt contains (24) hourly sensor readings over a 12-day period.

Sensor readings are in the range 0-9.

$ wget https://code.kx.com/download/learn/iteration/sensors.txt

--2022-01-03 11:27:18-- https://code.kx.com/download/learn/iteration/sensors.txt

Resolving code.kx.com (code.kx.com)... 74.50.49.235

Connecting to code.kx.com (code.kx.com)|74.50.49.235|:443... connected.

HTTP request sent, awaiting response... 200 OK

Length: 300 [text/plain]

Saving to: ‘sensors.txt’

sensors.txt 100%[===================>] 300 --.-KB/s in 0s

2022-01-03 11:27:19 (143 MB/s) - ‘sensors.txt’ saved [300/300]q)show s:read0`:sensors.txt

"030557246251157265736086"

"757251109999993270188377"

"776439448625126896347568"

"116491158137137589031187"

"855938799541699262946623"

"104948806186867057936025"

"328964479858696484945053"

"861596102999933729145653"

"623589072102430497578780"

"240663439999997746246672"

"311551572414272384005263"

"850884046457214232200714"a. For each of the 24 hours, on how many days of the period did the sensor reading for that hour fall to zero?

Converting the sensor readings to numbers is not necessary: they can be compared directly to "0".

q)s="0"

101000000000000000000100b

000000010000000001000000b

000000000000000000000000b

000000000000000000100000b

000000000000000000000000b

010000010000000100000100b

000000000000000000000100b

000000010000000000000000b

000000100010001000000001b

001000000000000000000000b

000000000000000000110000b

001000100000000000011000bs. Each item (row) is a character list (string) and Equals continues iterating through the items.

The result of s="0" is a boolean matrix of the same shape as s.

Summing it simply adds the rows together.

q)sum s="0"

1 1 3 0 0 0 2 3 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 2 2 1 3 0 1iYour maintenance manager gets automated reports printed, but the last report got damaged. She needs your help.

b. On which days did the sensor readings begin (8, 6, 1, 5, …) and (1, 1, 6, 4, …)?

We can search the first four columns of s for these sequences.

q)s[;til 4]

"0305"

"7572"

"7764"

"1164"

"8559"

"1049"

"3289"

"8615"

"6235"

"2406"

"3115"

"8508"q)s[;til 4]?("8615";"1164")

7 3Visualizations help us find patterns in datasets. Even simple visualizations can be valuable.

Normal operating levels are in the range (2,7).

c. Display a simple plot showing when the sensors reported levels outside that range.

The within keyword take as right argument a 2-item vector of sortable type.

It has atomic iteration in its left domain.

Keyword not is atomic.

q)not s within "27"

101000000001100000000110b

000001111111110001111000b

000001001000100110000001b

110011101100100011101110b

100101011001011000100000b

110101110110100100100100b

001100001101010010100100b

101010110111100001100000b

000011100110001010001011b

001000001111110000000000b

011001000010000010110000b

101110100000010000011010bBecause Index At is right-atomic we can use the boolean matrix to index a string.

".#"not s within "27"

"#.#........##........##."

".....#########...####..."

".....#..#...#..##......#"

"##..###.##..#...###.###."

"#..#.#.##..#.##...#....."

"##.#.###.##.#..#..#..#.."

"..##....##.#.#..#.#..#.."

"#.#.#.##.####....##....."

"....###..##...#.#...#.##"

"..#.....######.........."

".##..#....#.....#.##...."

"#.###.#......#.....##.#."At level 9 productivity is highest.

d. Plot when in the period this occurred.

".#"s="9"

"........................"

"........######.........."

".....#..........#......."

"....#............#......"

"...#...##....##...#....."

"...#..............#....."

"...#....#....#....#....."

"....#....####....#......"

".....#..........#......."

"........######.........."

"........................"

"........................"Implicit accumulator iterations¶

Accumulator iterations evaluate some expression successively: the result of one evaluation becomes the argument of the next.

We have already used the sum keyword, which implicitly evaluates Add between successive items of a list.

q)((2+3)+4)+5

14

q)sum 2 3 4 5

14

q)a:`cats`dogs!2 3; b:`cows`sheep!3 4; c:`dogs`sheep!5 6

q)sum (a;b;c)

cats | 2

dogs | 8

cows | 3

sheep| 10sum is an aggregator: it returns the result of its last evaluation.

sums also iterates successively, but returns the results of all the evaluations.

q)(2;2+3;2+3+4;2+3+4+5)

2 5 9 14

q)sums 2 3 4 5

2 5 9 14sums is a uniform function.

Notice also that the index of the result corresponds to the number of evaluations: (sums 2 3 4 5)[3] is the result of three additions and (sums 2 3 4 5)[0] is the result of no additions.

Keywords such as mavg and msum combine map iterations (e.g. evaluate on each group of three successive items) with an aggregator which might employ accumulator iteration, e.g. sum.

q)3 msum 1 5 0 9 5 2 2 4 0 5 3 0

1 6 6 14 14 16 9 8 6 9 8 8Exercise 2¶

Factory productivity is thought to be most affected by the machinery’s fuddling level. An automated process adjusts the fuddling level every 20 minutes to keep it stable; the level resets to zero each midnight.

We have in fudadj.csv a log of the adjustments.

q)\wget -q https://code.kx.com/download/learn/iteration/fudadj.csv

q)read0 `:fudadj.csv / fuddling adjustments

"-1,-1,3,3,2,3,3,3,1,-1,3,0,2,1,2,1,0,-1,3,0,3,1,1,1,3,0,-1,3,-1,2,0,2,1,3,0,0,0,..

"0,1,-1,-1,3,-1,-1,3,1,1,2,1,-1,1,3,2,2,3,2,2,2,3,3,3,2,3,0,3,3,1,2,1,-1,-1,-1,0,..

"1,0,-1,2,3,-1,1,-1,-1,-1,2,3,2,0,0,3,3,2,2,-1,2,-1,2,0,1,2,2,0,0,-1,1,3,-1,1,-1,..

"3,2,2,1,3,-1,-1,-1,1,-1,1,1,0,-1,0,3,-1,0,2,0,2,0,1,2,3,2,1,3,-1,2,-1,1,2,1,-1,3..

"1,0,3,-1,2,3,3,1,1,2,-1,1,1,3,-1,2,2,2,2,2,0,3,-1,1,2,-1,3,0,0,1,2,3,3,0,-1,0,-1..

"2,-1,3,2,1,2,3,3,1,2,-1,-1,1,-1,0,-1,3,2,-1,-1,-1,1,1,2,2,3,0,2,1,0,1,2,3,3,2,-1..

"3,1,-1,2,1,3,-1,1,0,1,2,2,1,3,1,1,1,3,2,-1,-1,1,0,3,3,0,0,2,1,0,2,3,2,2,2,0,-1,-..

"-1,2,-1,-1,1,2,-1,0,2,3,0,2,0,1,2,-1,3,3,1,2,-1,-1,-1,3,3,0,1,1,1,3,2,1,-1,1,2,2..

"-1,3,-1,2,0,0,1,1,1,3,0,2,2,2,2,-1,-1,-1,-1,1,1,3,0,3,-1,1,2,3,0,-1,2,2,2,2,0,2,..

"3,2,-1,-1,0,-1,3,2,0,3,1,0,0,2,3,2,1,1,-1,2,3,-1,3,3,3,-1,1,3,2,1,1,1,2,3,2,1,1,..

"0,2,0,1,-1,3,0,2,-1,2,-1,2,0,0,-1,3,0,3,1,0,2,2,3,-1,2,0,1,1,2,0,2,2,0,0,0,-1,1,..

"2,-1,2,-1,3,0,1,1,0,-1,2,2,3,3,0,0,-1,1,3,-1,1,2,2,3,2,-1,0,2,0,3,0,1,1,0,3,3,-1..What were the fuddling levels corresponding to the sensor readings in Exercise 1?

The file has no column headers, so Load CSV returns not a table but a list of columns.

q)show fa:(prd[24 3]#"J";csv)0: read0 `:fudadj.csv / fuddling adjustments

-1 0 1 3 1 2 3 -1 -1 3 0 2

-1 1 0 2 0 -1 1 2 3 2 2 -1

3 -1 -1 2 3 3 -1 -1 -1 -1 0 2

3 -1 2 1 -1 2 2 -1 2 -1 1 -1

2 3 3 3 2 1 1 1 0 0 -1 3

..That suits us. The 72 rows correspond to 20-minute intervals. We take cumulative sums across the intervals, and select every third sum to get the hourly levels. Transposing the result gives us 12×24 fuddling levels.

q)flip sums[fa]@2+3*til 24

1 9 16 18 23 23 29 32 34 38 41 44 44 50 52 54 59 62 65 72 72 76 78 80

0 1 4 8 11 18 24 33 38 45 47 45 50 51 54 55 58 58 57 61 64 68 69 66

0 4 3 7 9 17 20 21 26 25 28 27 28 33 34 34 36 42 46 49 51 55 55 61

7 10 9 10 9 11 15 18 24 28 30 33 35 41 41 43 43 49 51 56 57 57 62 63

4 8 13 15 18 24 28 31 35 36 44 43 45 47 49 55 58 60 64 62 65 67 68 70

4 9 16 16 16 20 17 21 26 29 35 39 42 49 57 59 65 69 73 73 75 74 74 77

3 9 9 14 19 24 24 28 31 34 41 45 46 49 55 57 59 62 68 71 75 77 79 79

0 2 3 8 11 16 18 19 23 28 30 35 36 37 41 41 42 47 54 59 58 59 63 67

1 3 6 11 17 14 15 21 23 25 31 35 41 46 47 51 54 59 63 67 73 77 81 86

4 2 7 11 16 20 24 29 32 38 42 48 51 56 60 67 64 72 75 78 79 82 85 91

2 5 6 9 8 14 17 21 24 27 31 30 32 36 38 39 41 44 42 47 50 50 51 53

3 5 7 10 16 16 19 26 27 32 34 40 39 40 43 51 51 53 57 62 65 63 65 71It is clear that the automatic adjustments are not keeping the fuddling levels stable.

Yet another way q is weird?

If in other languages you are used to specifying iterations, you may at first experience this as an annoying distraction. Besides solving your problem, you also have to learn and keep in mind q’s implicit iterations. You already know how to write iterations. Why now learn this?

The reward is that, as implicit iteration becomes familiar to you, you stop thinking about most of the iterations in your code, which leaves you more mental space for problem solving. (Only when we put on noise-cancelling headphones do we discover how much annoying background noise we had been filtering out.)

As a bonus, many algorithms are startlingly simple to write in q. It’s way cool.

Conclusion¶

That’s it. The big takeaway is that there is a lot of iteration built into the q primitives. It will almost always give you your shortest, fastest code – and the most readable.